This past year of dealing with the viral pandemic has been a challenge for us all. I’m sure we all discovered just how much the e-charged world means to us. It has been our thread to every kind of connection–human, business, entertainment, and news. The lack of face-to-face contact with family and friends, the restrictions to just about everything and the fear of the unknown presented me with new opportunities despite the restrictions.

Lucky me, living in Florida with almost daily sunny weather, having my studio at home and the company of my wonderful Blue Heeler Opus has gotten me through most of the obstacles and insane politics of 2020. In fact, life hasn’t been really that much different for me, but boredom and frustration did take hold often. With so much unstructured time, I found myself doing a lot of introspection and contemplating back-burner projects.

One unintended project was to begin a memoir. Writing this memoir has been a gift–a gift to myself–replaying the tapes of my life–replete with challenges, mentors, misfires, successes and a large dose of serendipity–-all of which sculpted me into the artist I’ve become.

In 1995, one year before his death, my father asked me to look over a rather large bound manuscript of a book he wrote about Picasso. One that was not at all favorable. He called it Anatomy of a Hoax, claiming that Picasso stole most of his ideas and styles from other artists–living and dead. He held Picasso personally responsible for what he saw as the travesty of art that dominated museum walls and galleries from approximately 1920 through the 1960’s and beyond. Modern art. It was an enterprise that consumed him. Ok, it was a crusade! He actually got me involved (reluctantly) in doing most of the paste-up for his book when I was an adolescent. The book was never published and after Dad died the manuscript took up residence in the back of my office closet.Over the years, I have flirted with the idea of bringing this wealth of material to fruition because I believed Dad was really onto something, but my own work and life preempted such an undertaking until being quarantined at home during the pandemic and finally having the time to get going on it. What I didn’t realize when I began to revise Dad’s introduction to Anatomy of a Hoax was that it would lead to the telling of my own story—of becoming an artist—a painter—and the challenge of growing up with my brilliant, complicated and domineering father.

Dad was a surgeon as well as a painter and I was privileged to grow up in a home surrounded by art. He also dragged me through art museums during family trips. It was abundantly clear that ART meant traditional art to my father. But given my independent nature I began seeing paintings and sculpture through a fuller spectrum with my own eyes, not seeing art through my ears as was always Dad’s intent. He was quite the art historian and filled me with much more information than I could possibly absorb. I definitely went into resistance mode.

My own senses and passion for art were awakened as an art student at the University of Illinois. It was all about finding my own voice, reaching deep into myself to discover what or who might inspire me and taking the artistic career plunge. Beginning a painting and facing a white canvas is never the same, never easy and always a bit intimidating. Kinda like stage fright. Can I make this happen? Can I bring my idea to fruition? How/when/where do I put that first charcoal line or brushstroke down on canvas? It’s the biggest commitment regardless of all the changes and experimentation that ensue. And with each painting there is always a pause or a stage when no matter how much time I have spent on it or think I’ve got it all figured out or when I catch my ego inflating, it’s time for a reality check.

Increasingly, I have focused, or should I say been bombarded by what is going on all around me in the environment–both globally, locally, politically. Not a pretty picture. Challenging subject matter indeed.

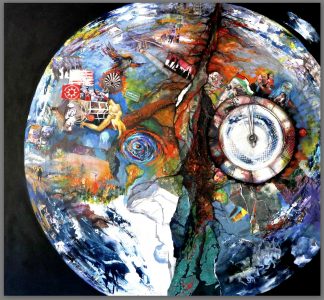

The world seems to be discharging so many climatic and human tragedies to which the media exposes us hourly and by the Tweet. There seems to be no letting up. Gradually, an idea for a painting began to germinate. I knew what the title would be before I made a single mark on the canvas–QUAKE.

As Opus and I took our morning walks through the neighborhood I paid close attention to cracks, lines and potholes in the streets, memorizing their lines and patterns with my phone as back-up. This painting needed to be large. The sphere of the earth was where I started, deliberately situating it off balance. Next came the giant fissure representing a major quake–the fault line–dividing the canvas vertically. People and events appear along and around the many fissures that radiate from the earth rupturing.

After a few months of working on QUAKE, I found myself getting really depressed. So many apocalyptic issues. I couldn’t help but experience the vibrations and intensity of all I was representing visually. I actually counted the issues once. TWENTY! Fires, hurricanes, devastation in Gaza. Yemen, Syria, asylum seekers along the U.S. border, homelessness and police brutality–to name a few. Like looking through a kaleidoscope at the earth sustaining a quake. The world as we’ve known it under siege.

After a few months of working on QUAKE, I found myself getting really depressed. So many apocalyptic issues. I couldn’t help but experience the vibrations and intensity of all I was representing visually. I actually counted the issues once. TWENTY! Fires, hurricanes, devastation in Gaza. Yemen, Syria, asylum seekers along the U.S. border, homelessness and police brutality–to name a few. Like looking through a kaleidoscope at the earth sustaining a quake. The world as we’ve known it under siege.

One day I turned on Democracy Now (my go-to news source). Noam Chomsky–renowned American linguist, philosopher, historian, social critic, and political activist, was giving a lengthy interview. He spoke of the ‘Doomsday Clock,’ the symbolic clock which represents a two-minute to midnight countdown to potential global catastrophe. I HAD to include this clock in the painting. It not only punctuated my thoughts and imagery but helped to visually balance QUAKE’S overall design.

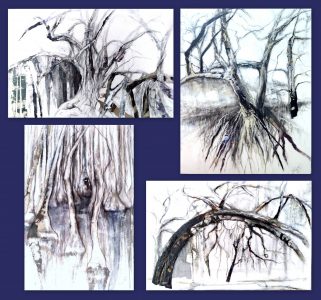

I realized it was time to get past the doomsday scenario somehow, to complete this work, move on and change the subject for a time. I needed to suspend my focus on so many dire issues and lift my spirits. The best way for me to do that was to turn to nature–always restorative and life-affirming. QUAKE is not only complex in subject matter but also in color. The prospect of working in only black and white was enticing, but I couldn’t help myself from adding a tinge of sepia, a red line or a Prussian blue wash. Working on a new surface (to me) of pre-gessoed small-scale wood panels offered a challenge. The ultra-smooth surface of the panels is perfect for multi-media–charcoal, water-soluble graphite pencils, acrylic and of course colláge. I make most of my own colláge materials, brushing and scraping acrylic paint around abstractly on archival paper that I can later tear up and incorporate into a painting or drawing.

Tree Series in Black and White

Marsha Glazière 2021